Status:

14.5 Directional Derivatives and Gradient Vectors

In considering the rate of increase/decrease of a function of several variables at a point, the direction plays a role. In section 14.3, we focused on the special directions along each of the coordinate axes, which introduced the partial derivatives; but we need to compute the rate along any direction. For a function of two variables defined near , take any direction , the rate of change of at in the direction of is if it exists, and will be denoted as . Once is given, this becomes a one-variable calculus problem. Since there exists infinitely many directions, do we need to do this computation for every ? Some of the questions that we need to address include:

- Is there a simple dependency of ?

- What’s the meaning of direction of steepest ascent/descent? What about directions such that ?

The motivation for directional derivatives (all of the stuff above the definition) is useful for visualizing what’s going on. Please read it.

It turns out the notion of the gradient plays a crucial role in answering the above questions. By definition, it looks like we are just giving a name to the vector whose components are the partial derivatives of a function. But this vector has some amazing properties which will allow use to find directional derivatives, paths of steepest ascent, and normal vectors to level curves and surfaces. The gradient will also be a critical tool that we use to analyze vector fields in chapter 16.

Find the following definitions/concepts/formulas/theorems:

- directional derivative (definition and formula (3) or (4) for finding it using the dot product — but this needs the differentiability of at the point)

- The derivative of at in the direction of the unit vector is the number provided the limit exists. It is also denoted as (read as “The derivative of in the direction of , evaluated at )

- properties of the directional derivative

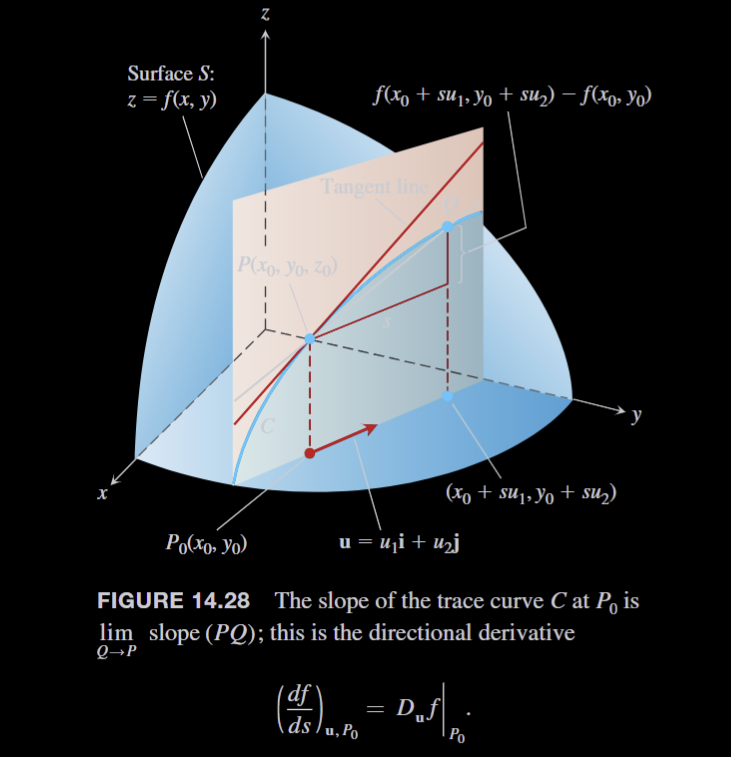

- The equation represents a surface in space. If , then the point lies on . The vertical plane that passes through and parallel to intersects in a curve (Figure 14.28). The rate of change of in the direction of is the slope of the tangent to at in the right-handed system formed by the vectors and .

- The function increases most rapidly when , which means that and is the direction of . That is, at each point in its domain, increases most rapidly in the direction of the gradient vector at . The derivative in this direction is

- Similarly, decreases most rapidly in the direction of . The derivative in this direction is

- Any direction orthogonal to a gradient is a direction of zero change in because then equals and

- tangent line to a level curve- Big question: what would you get if you extended this formula into ? What would the formula be, and what would it represent? Could you keep going into higher dimensions?

- If you extend this formula into , it would not be the equation for a line; it would be the equation for a plane:

- Algebra rules for gradients

- Sum rule:

- Difference rule:

- Constant multiple rule: (any number )

- Product rule:

- Scalar multipliers on left of gradients

- Quotient rule:

- Scalar multipliers on left of gradients

- extension of gradient into three dimensions

- Chain Rule for Paths

- If is a smooth path , and is a scalar function evaluated along , then according to the Chain Rule, Theorem 6 in Section 14.4,

Example 1 is a direct calculation using the limit definition of the directional derivative. Please don’t ever calculate a directional derivative this way if you can avoid it. Example 2 is how you should be calculating directional derivatives.

Example 3 illustrates how the gradient relates to the direction of greatest increase/decrease and the directions of zero change (which are tangent to the level curve or surface as one would expect).

Example 4 shows how to use the gradient to find the tangent line to an implicitly defined curve in . What we are really doing in this example is “going up a dimension” to think about this 2D object as a level curve of some 3D object. We certainly could use calculus 1 implicit differentiation techniques to find this tangent line, but the calculations are much faster and cleaner this way.

Example 5 applies the algebra rules in a couple of typical ways. There should be no surprises here. Example 6 is a straightforward application of the gradient for a function of three variables. Directly above example 6, there is a sentence that says, “In any direction orthogonal to , the derivative is zero.” How many such directions are there? If you put all of those directions together, what shape do you get?

Reading Questions/Quizzes

- Let .

- Compute the directional derivative of at in the direction of .

- Compute the gradient vector of at .

- Sketch the gradient of at together with the level curve that passes through this point.

- TK

- Find an equation of the tangent line to the level curve of that passes through .

- Find the direction of steepest ascent of and direction of steepest descent at .

- . The direction of steepest ascent is and the direction of steepest descent is .

- Find an equation of the tangent plane to the graph of at . Identify its normal vector.

- TK

- Compute the directional derivative of at in the direction of .