Status: Baby

14.2 Limits and Continuity in Several Variables

In Calculus I (probably in Precalculus as well), you learned about limits and continuity. When

you defined , you were told that in order for this limit to exist that the two one-sided

limits had to exist and be equal. And then you were told that in order for a function to be

continuous at some point that and both had to exist and they had to be

equal.

In multi-dimensions the limits are very different in one particular way. When you only have

one real input variable, your domain is just part of the number line. If you look at a point on

the number line, there are only two ways to approach it: from below (or left) and from above

(or right). But if we are talking about , the domain is some part of the plane . For

an arbitrary point in the middle of your domain, there are infinitely many paths that you can

follow to get there. The limit only exists if it is the same on any of these infinitely many paths.

Since there is no good way to enumerate these infinitely many paths, the proper way to describe

a function having a limit at some in the domain is as done in the Definition at the

beginning of the section.

In situations where exists, the continuity condition is straightforward to check. To show that f (x, y) is not continuous at , one has to show that either does not exist or it does exist but not equal . The first possibility is often harder to address (read the Two-Path Test)

Find the following definitions/concepts/formulas/theorems:

- Limit of a function of two variables (- definition)

- Suppose that every open circular disk centered at contains a point in the domain of other than itself. We say that a function , approaches the limit as approaches and write if, for every number , there exists a corresponding number such that for all in the domain of , whenever

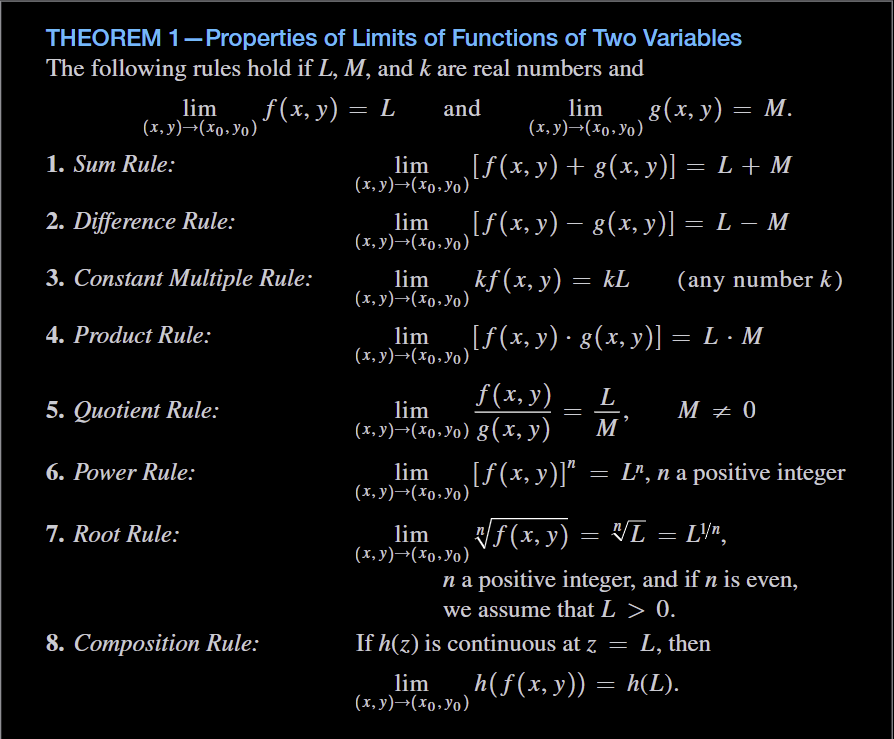

- Theorem 1: Properties of Limits (functions of two variables)

- Techniques for showing that the limit of a function of two variables does not exist (Two-Path Test)

- Take the limit of the function as it approaches from two or more paths.

- If a function has different limits along different paths in the domain of as approaches , then does not exist.

- Continuity (functions of two variables)

- Suppose that every open circular disk centered at contains a point in the domain of other than itself. Then a function is continuous at the point if

- is defined at

- exists

- A function is continuous if it is continuous at every point of its domain

- Suppose that every open circular disk centered at contains a point in the domain of other than itself. Then a function is continuous at the point if

- Continuity of compositions of continuous functions (this part is the same as for the one variable case)

- As with the definition of limit, the definition of continuity applies at boundary points as well as interior points of the domain of .

- A consequence of Theorem 1 is that algebraic combinations of continuous functions are continuous at every point at which all the functions involved are defined. This means that sums, differences, constant multiples, products, quotients, and powers of continuous functions are continuous where defined. In particular, polynomials and rational functions of two variables are continuous at every point at which they are defined.

- If is continuous at and is a single-variable function continuous at , then the composition defined by is also continuous at

- Limit of a function of three variables

- The definitions of limit and continuity for functions of two variables and the conclusions about limits and continuity for sums, products, quotients, powers, and compositions all extend to functions of three or more variables

- Extreme Value Theorem (multivariable edition; the new ingredient is the domain must be a closed bounded set)

- The Extreme Value Theorem (Theorem 1, Section 4.1) states that a function of a single variable that is continuous at every point of a closed, bounded interval takes on an absolute maximum value and an absolute minimum value at least once in . The same holds true of a function , that is continuous on a closed, bounded set in the plane (like a line segment, a disk, or a filled-in triangle). The function takes on an absolute maximum value at some point in and an absolute minimum value at some point in . The function may take on a maximum or minimum value more than once over . Similar results hold for functions of three or more variables. A continuous function must take on absolute maximum and minimum values on any closed, bounded set (such as a solid ball or cube, spherical shell, or rectangular solid) on which it is defined. We will learn how to find these extreme values in Section 14.7.

- Important: There is a technique for showing that a limit (of a two-variable function) exists by using the Sandwich Theorem (a/k/a the Squeeze Theorem). Note that this technique does not appear in the main body of the section. It is on page 822, below exercise 58. Please read it, and we will discuss it in class.

- TK

- Important: There is a technique for showing that a limit (of a two-variable function) exists by switching to polar coordinates. Note that this technique does not appear in the main body of the section. It is on page 822, below exercise 64. Please read it, and we will discuss it in class.

- TK

Examples 1 and 2 are short and direct applications of rules to (reasonably) well-behaved functions. Make sure that you look at the justifications carefully, though. One of the most common errors on this type of question is applying some limit law or theorem incorrectly and getting a value for a limit when the limit does not actually exist. Example 2 has a peculiar feature that the textbook didn’t address: the function is defined only for and , and is not an interior point of the domain of definition of this function; however, the technique for dealing with this quotient of form is worth pondering—l’Hopistal’s rule does not apply in this multi-dimension setting.

Example 3 uses the - definition to find the limit. This problem is much easier by converting to polar coordinates, which we will do in class, because the condition is most naturally expressed as in polar coordinates. Example 4 uses the - definition to show that a limit does not exist. I do not expect you to apply the - definition on quizzes or exams. Example 5 is a standard example of how you go about testing continuity at a point in the domain of a multivariable function. Example 6 uses the Two-Path Test to show that a limit does not exist.

It’s very nice when you find two different limits as you approach the point on two different lines or curves. The frustrating part is that sometimes you consider lots of different paths and get the same limit every time, but you can’t find one that’s different. And you also can’t find a theorem that tells you that the function actually has a limit. This is what a lot of higher level math (and much of mathematical research) is like. You try to prove that something is true for a while and can’t. Then you spend some time trying to find a counterexample that shows the something is false and you can’t. But some of the counterexamples you tried gave you a new technique that you use to try and prove the theorem… and you still can’t prove the theorem. But it is very satisfying when you end up with either a valid proof or a valid counterexample after a long struggle.

Reading Questions/Quizzes:

- What rules of Theorem 1 allow one to draw quick conclusions on the limit

- Utilizing the power rule, this can be simplified into squaring the limit of just the inside of the parenthetical

- What rules of Theorem 1 allow one to draw quick conclusions on the limit

- Using the product rule, this limit can be found by splitting it into two different limits, with the first being the limit of and the second being the limit of

- By considering different paths of approach, show that the function does not have a limit as

- With the path as , the limit evaluates to . However, with the path as , the limit evaluates to . Therefore, the limit does not exist.